There were living in the 18th century two John Balchens, both of whom were naval captains. The first and the most famous was Admiral Sir John Balchen, born February 1669/70 and who died by drowning on 4 October 1744 at the age of 77.

The other John Balchen was Captain John Balchen of the East India Company who was born on 29 August 1696 and who died, of a fever, on 26 July 1742 at Canton, China, at the age of 45.

Thus although the older John Balchen was born 26 years before the younger one, the younger John Balchen died two years before the older one.

And, for 26 years, the two John Balchens enjoyed parallel successful naval careers, one with the Royal Navy and the other with East India Company. It is perhaps not surprising then that the identities of these two men have sometimes been merged and it is the purpose of these pages to entangle the one from the other and to clearly distinguish between them.

Although Mary (Balchen) Man and her sister Elizabeth (Balchen) Cumberland were fond of styling themselves as ‘nieces’ of the admiral Sir John Balchen, and on occasion directs descendants, nonetheless it is safe to say they were not his nieces and instead, based on very careful genealogical research, they were the nieces of the younger John Balchen, the East India Company captain. The various (false) claims of a relationship between ‘our’ Balchen family to that of the Admiral’s have been gathered and can be read HERE (<— in pdf).

An example of the Balchen ladies over reach can be seen in this confusing and misleading marriage announcement below of 21 September 1749 in the Whitehall Evening Post. It is confusing because the Balchen who married George Cumberland was Elizabeth and not her sister Ann. It is misleading too because neither Ann nor her sisters were nieces of the admiral’s.

William Man’s Letter to Edward Garnet Man.

The following letter was written by William Man, son of John Man, to Edward Garnet Man. William and Edward would have been first cousins one generation removed; William being the first cousin of Edward’s father Harry Stoe Man.

In this letter, William’s recollections are somewhat accurate, however his claims about Admiral Balchen are not since NO relationship, at least not nearly as close as William states, has been established between the Admiral’s family and the London Balchen family of William’s grandmother Mary (Balchen) Man. The journal mentioned by William and kept by James Balchen (NOT a Sir) can be found here. James Balchen was Mary Balchen’s brother and therefore William’s great uncle and he certainly was neither a brother nor a son of the admiral’s. ‘My cousin Ann’ refers to Eleanor Ann Rankin Man daughter of Henry Man. The grandfather William speaks of who dies in Wales is John Man.

47 Castle Street,

Reading Feb 10th, 1865

Dear Sir In reply to your letter received this morning being a total stranger to me, I find many incidents contained in it correct. I am uncertain whether my grandfather, who was a builder, and built many houses in that neighborhood, among others my father pointed one out to me then occupied by the Misses Dolbys built by him at Hurst. I formerly had an itinery written by Sir James Balchen, brother or son of the Admiral who was lost with his ship, of his journey to Hurst to pay a visit to his new relation Mr. Man and his wife, but whether senior or junior I have forgotten. I remember my father saying what a sever blow it was to his family the news of his Uncle Balchen the Admirals loss my Grandmother [Mary Balchen] being the Admiral’s sister. I heard my father say he himself was born in Goodman’s Fields (where probably my Grandfather lived) if so our Great Grandfather might have lived at Hurst. Further than this I know not. My Grandfather as you observed died in Wales. I believe at Cardiff. I have no knowledge of my Grandfather or Great Grandfather having lived in Cornwall. The itinery I mentioned still exists in the Man family. My cousin Ann, who you call Aunt, has made to me the same inquiries you are now making, who is now living at Halstead, Kent, with no better success.

Perhaps if you could find the year of the death of our Great Grandfather by searching his will at Doctors’ Commons, it might lead to something further.

I remain Dear Sir

Respectfully Yours

William Man

To E.G. Man, Esq.

The younger Captain John Balchen, of the East India Company sailed in a number of the company’s ships including the ‘James and Mary’ and the ‘Onslow’.

Two lists showing the East India Company’s ships, their tonnage and their captains as they are preparing for their outward voyages. Both lists contain roughly the same information and are dated 4 September 1727. Balchen’s ship James and Mary is the smallest at only 300 tons:

Notice indicating where each of the above ships has been selected to sail to. John’s destination is Bencoolen; dated 21 September 1727:

John’s return from Bencooleen is recorded in the London newspapers on a list of East India Company ships dated 20 March 1728. The captain’s log book for Balchen’s journey from 1724 to 1725 on board the ‘James and Mary’ can be read here (<— 191 pages).

This log is of interest as it describes the discovery on the Ascension island of the diary of a castaway Dutch sailor. This diary will be discussed in more detail below. The log also notes the death of Thomas Aubone, the captain of the ‘James and Mary’, and John Balchen becoming the ship’s captain. Below an announcement in a London newspaper dated 29 August 1734.

The log book of the ‘Onslow’ from 17 October 1734 through to 6 September 1736, and from 8 February 1738 through to 26 June 1739, and from 23 November 1740 through to 21 October 1743 can be read here (<— over 300 pages). The journal starts out with the Onslow under the command of Captain John Balchen and ends with a brief description of his death at Canton. The ship was then taken over by the Chief Mate, Ralph Congreve. Below an English newspaper’s report of John’s death:

It should be noted that some scholars of the admiral have been as guilty as the Balchen ladies when it comes to confusing the two ‘naval’ Balchens. For instance one scholar has speculated that when the vicar of St. Paul’s Covent Garden wrote the name of Sir John Balchen’s son as ‘Anesloe’ in the parish register what he meant to write was ‘Onlsow’ in the belief that Admiral Sir John Balchen had intended to name his eldest son after a ship that he had once served in. Unfortunately the Onslow was an East Indiaman ship not a Royal Navy vessel and only John Balchen the younger had served aboard the Onslow.

John’s will has been found and transcribed and can be read here. It should be noted that John mentions his three nieces: Mary (Man); Elizabeth (Cumberland); and Anne – further evidence that THIS John Balchen was the uncle of the Balchen girls and NOT the admiral.

In a volume entitled A biographical index of East India Company maritime service officers: 1600-1834 by Anthony Farrington there is a list of those who served as seamen for the East India Company and from this one can trace John Balchen’s career as follows: He made his first voyage as 4th Mate on board the ‘Thistleworth’ 1716-1717. He made a second voyage as 2nd Mate on the ‘Thistleworth’ 1718-19. He made two voyages on board the ‘James and Mary’ as 1st Mate. The first voyage was between 1720 and 1721 and the second voyage was between 1723 and 1724. He was Captain of the ‘James and Mary’ for two voyages 1727-1728 and 1730-1731. He then took command of the ‘Onslow’ and made three voyages as her Captain: 1734-1735, 1737-1738 and 1740-1741. The Onslow was one of the bigger ships on the East India Company’s navy weighing 480 tons, armed with 32 guns and with a crew of 98 men (according to ‘The Daily Journal’, September 7, 1734). In 1742 the Court Directors of the Honorable East India Company decided to send two delegations to Canton, China to discuss opening up trade relations. One sailed directly from London on board the ship ‘Defence’ and the other sailed from Bombay. John Balchen was in charge of the latter expedition, but he did not complete the journey as he died off the coast of Canton in July 1742.

Cambridge University has archives about the ‘Thistleworth’ but unfortunately these pre-date John Balchen’s time: 1714 – 1716 [Cambridge Univ Libr, Add 461 71]. We should also note that William Balchen (1722 -1765), John’s nephew, also enjoyed a naval career with East India Company. He sailed with his uncle John as 4th Mate on the ‘Onlsow’ 1740-1741. He was then promoted to 3rd Mate on board the ‘King William’ 1743-1744 and 2nd Mate aboard the ‘Exeter’ 1745-1746, eventually becoming a Captain. William’s will has been located and can be read here. The last member of the family to serve as an East India Company naval officer was Harry Stoe Man who served as a Purser on board the ‘Comet’ 1804-05. His service record continued aboard other ships but more research is needed.

We know from at least two newspaper accounts that in March of 1738 John Balchen faced a mutiny on board the ‘Onslow’. He appears to have been setting sail for Bombay and was probably heading out toward the English channel when the mutiny occurred. The papers say that the cause was over pay and that, although the East India Company had agreed to give the men of the Onslow 5s extra a month as a result of their complaint, still some had left the ship. It appears that some of those who had left were later caught. The newspapers speculate that the real cause was that the men did not want to fight in an upcoming war. What exactly this was has yet to be researched (stay tuned).

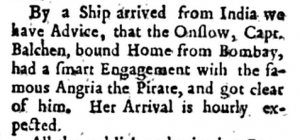

In 1739 we learn form the newspapers (below) that John Balchen was returning home from Bombay when he was approached by the famous Indian pirate Angria (or perhaps one of his sons Manaji or Sambhaji) and attacked. Fortunately Balchen managed to escape, but not before a ‘smart engagement’ with Angria which lasted several hours. The engagement may not have been as accidental as the papers reported, rather the encounter between Balchen and Angria may have been a part of the Bombay Government’s plan. We find that on the 6th October (1738) the company noted that: ” Manaji Angria’s galivats having a few days ago carried into Kolaba a batela which we suppose was coming to this island with grain and provisions, it is observed that our suffering such practices will deter the northern traders from venturing hither when they find they run so great a risk. It is therefore agreed that the new prahm and three galivats be ordered to lie at the mouth of the harbour between Kenery and the reef (the Prongs) to protect our own trade and prevent Manaji giving molestation to the vessels bound hither. On the 4th November [1738] Sambhaji Angria’s fleet being in sight and going into Kol’iba, Captain Balchen of the Onslow was ordered instantly to get his ship in readiness to proceed against the enemy.” Balchen’s engagements with the Indian navy were more than likely with the sons of Angria (Manaji and Sambhaji) as opposed to Angria himself who had by then retired. (Galivats, Batelas and Prahms are types of ship). Other newspaper mentions of John Balchen include:

The London Journal: The Ship James and Mary, Capt. Balchen, was arrived at Madras from Bencoolen, and was to load from thence for London, she having got but 50 Ton of Pepper at Bencoolen.

Parker’s Penny Post 1732 LONDON, August the 30. Tuesday last: a large Ship was launch’d at Blackwall and call’d the Onslow in Compliment to the Right Hon. the Speaker of the House of Commons. She is designed for the East India Company’s Service, and is to be commanded by Capt. Balchen. This Morning came into Harbour the La Juste Prize Captain Hall, from Antigua, taken by the Pembroke, Captain Balchen, laden with Sugar.

We also learn from the newspapers of the arrival at St Helena of John Balchen on board the Onlsow in May 1739 and of the loss of the East Indiaman Anglesea which was wrecked on rocks off the Malabar coast. The Angelsea was rated at 490 tons with 30 guns and 98 crew. She only made one voyage to Bombay, Madras and Bengal. Capt William Studholm her commander left the Downs on 2 Feb 1738 and the ship was wrecked on 23 Jul 1738 north of Goa, in ‘the Mallwan’s country’. In the churchyard of St Mary Magdalene, Bermondsey, there is a tombstone: ‘Mary, relict of Captain William Studholm, (1738)’.

John Balchen Discovers a Dutch Sailor’s Diary and its Subsequent History.

ROUGH DRAFT

Part One: The Discovery

John Balchen sailed into the bay of the Cape of Good Hope on Monday December 6th 1725 and wrote in the log book of the ‘James and Mary’ that:

‘At 4 yesterday in the afternoon The Sugar Loaf bore NEE distance Leagues and at 6 degrees the Sugar Loaf NE and Green Point bore ENE Distance 3 leagues At half past eleven in the night the body of Penguin Island bore ENE Distance 3 miles, at 5 this morning anchored in 7 fathom water, moored ship, Penguin bore NNE, Green Point NWW and the Sugar Loaf SW, Charles Mount SWW, the Fort SSW Distance from the bridge 3 miles. Saluted the Fort with 9 guns they returned the same, found riding here the Compton who left Madras in Company with us and arrived at this place three weeks and four days before us, found lying here two Pairs of Dutch Ships outward bound, struck yards and top masts, the winds from NW to WSW the weather fair, this evening James Robbinson departed this life. [Page 154 on original pdf document]

Tuesday 7th Close weather for the Major part with moderate gales of wind between the South and East Sailed the Compton Captain Mawson for St. Helena, saluted him with five guns he Returned the compliment, the longboat made two trips for water, keep the people employed in fitting the rigging and securing the gamoning [?] of the bow spit, the knee being lose by the loss of our Head ……[?]

Wednesday 8th This 24 hours the weather fair the winds variable all round, the longboat made two trips for water.

On the 12th Balchen sent half the ships crew on shore supposedly to enjoy the comforts found on land.

[This activity of sending the long boat out for water and repairing the rigging continues until the 14th when Balchen states that “at 10 this morning I came on board, unmoored and got all Ready for Sailing”. On Wednesday December 15 1725 the log notes that “Sugar Loaf bore SE at distance of 10 leagues from which I take my Departure allowing it Lay in the Latitude.”

The ‘James and Mary’ sailed on toward its home port of London and as it did so it approached Ascension an uninhabited island except for birds and turtles. These latter creatures were often captured by passing ships’ crews by being turned upside down and brought on board ship, kept alive there and later killed and eaten.

On Thursday January 20th 1725/26 Balchen writes:

Fair weather the winds between the S and E:, At 3 yesterday in the afternoon anchored on the NW side of the Island Asscesion. Distance off shore one mile Depth of water 30 fathoms, fine black (?) Ground, here is a fine sandy bay and good landing with your boats, sent our boat on shore to Turn Turtles, …this morning the boat returned on board with two, Left eight on the shore which we fetched off afterwards, here we found a tent with Bedding and Several Books with some writings by which we find there was a Dutch man turned on Shore here out of a Dutch ship for being guilty of Sodomy in Last May. Could not find him so believe he perished for want of water, the Compton is now on the heel a stopping her leak. This evening sent people on Shore to turn Turtles. [Page 174 on original Log in PDF]

Friday January 21 Little winds and fair weather, This morning sett up our fore Shrouds, missed one John Drury. Searched the Ship but could not find him, believe he drowned him self in the night he being Lunatic for some time, this evening the Compton made an end stopping their leak and getting all Ready for Sailing in the Morning ….

Captain Mawson’s description of the discovery of the Dutchman’s camp and belongings is similar to Balchen’s however unlike Balchen he is unable to state what the crime was that had caused the Dutchman to be cast upon the Island. Mawson wrote that ‘.. we have no Dutch enough among us to read them’. The fact that Balchen described the diary, in part, indicates that he did have access to a Dutch speaker.

John Balchen’s mention of the ‘Compton’ taking on water occurs only in the passage dated January 20 quoted above. However from other sources we learn that the ‘Compton’ had been in trouble for some time. For instance in ‘A Dutch Castaway’ Alex Ritsema writes:

Captain William Mawson and his crew had a serious problem: The ‘Compton’ was severely leaking … Fortunately the ‘Compton’ remained within view of another East India ship, the ‘James and Mary’ commanded by Captain John Balchen who had been one of Mawson’s highest-ranking officers some months before but became captain of the ‘James and Mary’ when her captain Thomas Aubone died at sea on 19 August 1725. The two Captains decided to keep their ships together and on 15 January Captain Mawson was temporarily on board the ‘James and Mary’ (This fact probably came from the Compton’s log as Balchen does not mention this). Doubtless the two captains thought of the possibility that all the people on board the ‘Compton’ might have to move to the ‘James and Mary’. On January 15 both ships changed course for Ascension Island, where the ‘Compton’ had to be made seaworthy again. On the afternoon of January 19th the two ships anchored in Clarence Bay.

Ritsema’s claim that John Balchen transferred from the ‘Compton’ to take over the position of Captain on the ‘James and Mary’ is not supported by any mention in the log of the ‘James and Mary’. Indeed John Balchen is listed as Chief Mate of the ‘James and Mary’ on her outward bound voyage. He was thus promoted from within rather than being transferred from the Compton.

As for the death of Thomas Aubone, which paved the way for Balchen to rise to Captain, the following account in the log book of the ‘James and Mary’ can be found:

Log Thursday August 11 Fair weather all the Day, winds from W to South with a tumbling southern swell, in the night squall and Rain, winds from SE to SW. about forty minutes past ? in the evening Departed this Life Thomas Aubone, commander at Eggmore Fort.

Friday August 20th Received on board several things belonging to the Captain. At half past 5 P:M the fort fired 12 Guns at the Funeral of our Captain We fired 18 and the Compton and Fordwich 12 Guns Each ….

To return to Ascension Island, at five in the morning the following day (Saturday 22 January) Captains Balchen and Mawson weighed anchor and set sail for England. Either on Balchen’s ship or on Mawson’s the Dutch sailor’s diary was securely aboard. The ‘Compton’ and the ‘James and Mary’ reached Woolwich on 9 April 1726 and 23 April, respectively.

Part Two: The Subsequent History of the Diary (the paragraphs below are heavily based on other people’s and need to be revised)

One year after Balchen found the Dutch sailor’s diary it was published under the title ‘Sodomy Punish’d: Being a True and Exact Relation of what befell to one Leondert Hussenlosch‘ (London, 1726). On the frontispiece there appeared a note that the diary had been found by ‘Persons belonging to an English ship Named the James and Mary’. This would suggest that Balchen kept the diary and may have been responsible for seeing that it got into the hands of a printer.

Two years later in 1728 the diary was published under the title ‘An Authentick Relation of the Many Hardships and Sufferings of a Dutch Sailor‘. This time the title page claims that the diary was ‘Taken from the Original Journal found …. by some sailors who landed on board the ‘Compton’, Captain Mawson Commander, in January 1725-26.’ What accounts for this change as to who found the diary is not possible to say, however given that the ‘Balchen’ version was published first would suggest that it was Balchen who kept the diary initially.

The quality of the translation is uncertain since the original diary has been lost. Apart from entries about desperate searches for water and firewood, a few entries mention the reason for the sailor being castaway and a few entries might be interpreted as reflections of a guilty conscience, including the apparitions of ‘demons’ and former friends and acquaintances.

In 1730 a more elaborate and embellished version was published under the title: ‘The Just Vengeance of Heaven Exemplify’d‘ (<— in pdf). This version contains many extra anti-sodomy passages as well as many more ‘demons’ harassing the castaway. The publisher also added that the castaway’s skeleton had been found alongside the diary. Clearly from John Balchen’s log no such thing was discovered.

So far, only one scholarly article has been found that discusses the history of the diary and this can be read here. This article was written prior to the discovery that it was Balchen and Mawson who found the diary. As a result there is much speculation in the article that the diary and its discovery may have been a kind of forgery. The first edition of the diary published in 1726 can be read here, the second edition (1728) here. There was a third edition published in 1730.

Part Three: The Identity of The Dutch Castaway

The name of the Dutch castaway was Leendert Hasenbosch a Dutch soldier who went aboard a VOC-ship as the bookkeeper. Leendert Hasenbosch was probably born in The Hague (Holland, United Provinces) in 1695. When he was about fourteen years old, his father, his two elder sisters and his younger sister – his mother was already dead by that time – seem to have moved to Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies. At the end of 1713 Leendert Hasenbosch became a soldier at the VOC and went aboard a ship to Batavia (Jakarta).

From 1715 to 1720 he was a soldier in Cochin (a Dutch possession at the time) in India. In 1720 he returned to Batavia and was promoted to corporal, later to military writer (a sort of minor bookkeeper). At the end of 1724 he went aboard a VOC-ship as the bookkeeper (an officer) of that ship.

The ship made its compulsory stop at Cape Town Cape Town on 17 April 1725. On 5 May 1725 he was set ashore on Ascension Island an isolated island of volcanic origin in the South Atlantic Ocean, around from the coast of Africa, and from the coast of South America….

According to the diary, Hasenbosch started with a tent, an amount of water for about a month, some seeds, instruments, bibles or prayer books, clothing and writing materials. He made long walks over the barren island to search for water. However, he could find very little water and started drinking the blood of the green turtles and seabirds that he managed to kill, as well as drink his own urine. He probably died in a terrible condition after about six months.