On this page various writings by John Man (1749 – 1824) are reproduced. In Reading Library there are two volumes titled ‘Anecdotes’ which John had written out by hand and which were given to the library by a Mr. Stevens. These volumes can be read here:

Volume One and Volume Two. Fortunately, John’s writing is quite neat and can be easily read. Some of the sketches from the book can be found on this page.

John also published two books. The first was published in 1810 and titled ‘The Stranger in Reading’ which can be read here and the second was titled ‘The History and Antiquities of Reading: being a history of the town of Reading’ and published in 1816, but not yet available online. On the latter, one critic wrote:

Our great local historian, Charles Coates, whose ” History and Antiquities of Reading,” published in 1802, is so invaluable, must be mentioned. It is far superior to any other history of the town, and is a great contrast to Man’s History, which is poor, unreliable, and full of silly conjecture. (!)

When John’s The Stranger was published he must have been surprised at the amount of antagonism that it aroused among its readers and the population of Reading in general. An historian of Reading’s described the reception of the book as follows:

In the year 1810, a book appeared from the press of Messrs. Snare and Man, which made considerable impression on the minds of the people of this town, and touched severely some of their weak points. I refer to ” The Stranger in Reading,” a series of letters from a traveller to his friend in London. I do not think that the identity of the Stranger has ever been discovered; and perhaps it was as well for him that he remained incognito, or he might have suffered severely at the hands of the enraged townspeople. Amongst other playful reflections upon the state of the roads, the incapacity of corporations, etc., he remarks that he agrees with a traveller, who, after residing at Reading for a few days, said, “that the further he travelled westward the more he was convinced that the wise men must have come from the East ! ” He gives a sketch of the literature of Reading; but you will gather from the following statement that his remarks are not always to be depended upon : “The soil of Reading has not been very productive of men of genius, and the few names here recorded have added very little to the general stock of literature of the country. He rightly mentions that Robert Grosetete (Anglice Thickhead), Bishop of Lincoln, was consecrated here in 1235 : but adds the spiteful remark that the family of Thickhead must have been originally numerous, as many of their descendants are still to be found in various parts of the town.”

He concludes his sketch by a tribute of praise to Mr. Le Noir, who published several poems and prose works in 18o5, among which were Village Anecdotes (3 vols); and to Miss M. R. Mitford, who, in the words of the Stranger “is a young lady of great poetical talents, whose purity of sentiment and elegance of diction are equal to those of our best poets, while she excels most of them in the chastity of her style, and the harmony of her verse.” For once the Stranger appears to have been right in his judgment.

Another reference to ‘The Stranger’ can be found in the ‘Reading Handbook for 1906, listing historical accounts of the town’ and describing some of its literary products of the town says that ‘…there are Miss Mitford’s sunny sketches in ‘Belford Regis’, and there are the grey shadows thrown by ‘The Stranger’.’

Having published his book, John was roundly attacked and vilified by Henry Gauntlett (1762-1833) who angrily rebutted John’s views on religion in a series of relentless attacks in a book called ‘Letters to the Stranger in Reading’ . Gauntlet, a Methodist, took great offence at John’s views of Methodism and his book is one long lambaste. This book can be read HERE. In a memoir by Gauntlett’s daughter, Catharine, a brief reference is made to the conflict between John Man and her father.

In the seventh volume of Hacket and Laing’s Pseudonym Dictionary there is the following entry on p. 588: ‘John Man, Stranger (the) in Reading. Not by Rev. Henry Gauntlett but by John Man. See J.V. Guildling’s ‘Notable events in the municipal history of Reading’, 1895, p. 24. ‘Letter to the Stranger in Reading’ is a reply to the above and was probably by Henry Gauntlett’.

In 2006 John’s ‘The Stranger’ was reissued and edited by Reading historian Adam Sowan whose introduction gives some details of John Man’s life as follows:

John Man is now mainly known as Reading’s second historian. His very name sounds like a pseudonym – John Doe meets Everyman, perhaps – but he was real enough; what we know of him comes from his published and unpublished writings, occasional mentions and adverts in the Mercury, a very helpful website charting the family’s history, and a few other sources listed in the bibliography. He was born and baptised in Whitechapel in 1749, when his parents were living in Mansell Street, just outside the City of London. John was almost certainly educated alongside his brother Henry by the Rev. John Lamb at Whitgift School in Croydon. This is now a large and prestigious establishment, but in the 1760s it was in decline; its historian F H G Percy describes it as a small school for unambitious pupils. His brother Henry’s DNB entry refers to a nonconformist background which prevented him from entering a university; we know nothing more of young John’s life until he moved to Reading.

He arrived in 1770, and at some time within the next five years was appointed assistant master at William Baker’s Academy in Hosier’s Lane, north of Castle Street. This may well have been in 1773, when Baker felt obliged to publicly deny a rumour that he was about to retire. The introduction was possibly made by Henry Man, who was working in the City near Baker’s son, also William; the latter is mentioned in the Stranger’s Letter IV, and achieved sufficient fame as a printer to merit an entry in the DNB. In 1775 John married Baker’s daughter Sarah – his senior by nine years – and acquired a half share in the school. The couple soon had four children: Henry was born in 1776, William in 78, Anna Maria in 80 and Horace in 82. (Horace’s name may have been inspired by Sir Horace Mann – no relation – who in 1782 advocated a government of national unity; he was also an early devotee of cricket, and had played in Berkshire. This may be a clue to John’s opinions and interests.)

School Man

When Baker did retire, in 1779, he put a notice in the Mercury in which he begs leave to recommend Mr Man as every way qualified to succeed him, and it is from Man’s teaching career that we learn most about his character. In the late 18th century – and indeed until 1870 – no child was obliged to undergo any formal schooling. J M Guilding estimated that in 1812 some 900 children went to school when the population was about 11,000. The sons of the rich could go to Eton, Harrow and the like, which were taking custom away from local grammars such as Reading School (which was still officially ‘free’, but effectively charged fees). The poor had to rely on an assortment of charitable institutions; from Man’s History we learn that in 1809 there was one for boys, one mixed, and two for girls; one of these last he chides for being little more than a sweatshop producing cheap needlework. But times were changing fast: within two years both the Christian National (mixed) and the Lancastrian or British Schools (boys) had opened.

Between these extremes, the moderately well-off had a widening choice of private academies such as Man’s; most were single-sex, and boys of course fared better than girls. Baker had run his school since about 1740; Coates, in his History, describes him as ‘a man of amiable character and manners, of great classical and mathematical learning’. In 1773 he was boarding young gentlemen and teaching them writing, arithmetic, mathematics, Latin and Greek; young ladies had to be content with writing and accompts, i.e. household accounts. By the time Man took over, girls are no longer mentioned; the boys could also learn French, Italian, merchants’ accounts, the use of the globes, and natural shorthand; a few months later he added ‘every branch of useful and polite literature and dancing and drawing by the best masters’. Navigation joined the curriculum in 1782, and in 1786 he promises ‘mensuration in its various kinds’, geometry, trigonometry and geography; he stresses the importance of French since the signing of a new commercial treaty. His fees were 16 guineas a year; these, and the range of subjects offered, were very similar to other local schools. After his retirement, when he was seeking a new tenant-schoolmaster in 1799, he boasted that the house has been built within a very few years for the express purpose of a Boarding School, and has every accommodation for 40 pupils, with a good kitchen garden, and spacious play-ground walled in.

As well as Baker’s recommendation we have two or three other clues to what sort of schoolmaster – and man – Man was. In January 1782 the Mercury printed a letter from ‘An Advocate for a Liberal Education’ condemning corporal punishment in schools. This could have been written by anybody, but it followed four consecutive weeks’ adverts for Man’s school; and later that year he was seeking an English assistant ‘whose natural disposition will lead him to treat the young gentlemen with good nature, affability and affection’.

That Man himself embraced this ethos is evident from a pupil’s-eye view to be found in Reminiscences of a Literary Life (1836) by Thomas Frognall Dibdin (1776-1847), nephew of the composer Charles Dibdin. His memories of the school date from his fifth to eleventh years (c1781-87) when, as an orphan, he was sent to live with a great-aunt in Reading. With hindsight he was glad to have escaped Richard Valpy’s regime at Reading School; instead he joined Man’s ‘small establishment in an obscure part of the town’ on proportionately moderate terms. Dibdin paints an affectionate picture of his mentor:

‘He was a singular, naturally clever, and kind-hearted man: had a mechanical turn; and could construct electrifying apparatuses, and carve a picture frame’. (In 1778 a Mr Banks, ‘experimental philosopher’, was touring locally with scientific lectures and demonstrations featuring electricity. The Museum of the History of Science in Oxford has a number of ‘electrifying apparatuses’ dating from 1786; they were ‘popular with amateurs’.) Dibdin continues:

‘His studio, of this description, was at the top of the house; and many an hour do I remember to have spent therein, gazing with surprise and delight upon the mysteries of turning, planing and chisselling.’ The young Dibdin had to share a bed with John’s son Henry; he looked weak and emaciated, and tells us that ‘Mr and Mrs Man’s unremitting attention and kindness perhaps saved my life’. He was allowed to go into Man’s private room whenever he pleased. ‘It was sufficiently well filled with books here, for the first time, I caught, or fancied I caught, the electric spark of the BIBLIOMANIA. My master was now and then the purchaser of old books by the sack-full; these were tumbled out upon the floor, the arm-chair, or a table, just as it might happen.’ Dibdin was also welcome in old Mr Baker’s study. His ‘rapturous days’ at Reading included bathing in the Holy Brook at the Old Orchard, Coley Park. He says that by the time he left he had made ‘little progress in anything but writing, arithmetic and French’, but in no way blames Man for a defective education. He went on to become librarian to Lord Spencer, and among his own publications was indeed a volume entitled Bibliomania.

Barge Man

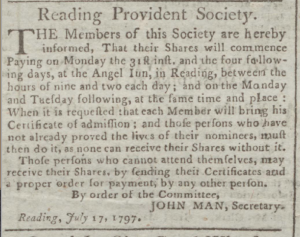

In the summer of 1795 Man retired, let the school to James Taylor, and moved to the High Street. He was only 45, and by no means idle: very soon he was Secretary of the Reading Provident Society, and within two years had embarked on a new venture in the growing business of waterborne transport.

The 54 years of Man’s residence in Reading span the great age of canal and river navigation. The middle Thames had been much improved by the building of eight new locks in 1772/3, and further enhancements were prompted by the threat of rival canals in the ‘mania’ of the 1790s. On 6 March 1797, ‘The Committee appointed to carry into execution the plan of a constant and regular Navigation between Reading and London, beg leave to inform the Public, that a Barge will lie at Mr Blandy’s Wharf [by the High Bridge] on Thursday next, to take in loading for London. Orders are received at the Counting-House in the Wharf, or at Mr Man’s’. Man’s partner was William Blandy, of the well-known local family, an ironmonger and coal merchant; the enterprise evidently became the Reading Navigation Company, which was still trading in 1800 with Man as Secretary. Man’s poem ‘The Counting House’ in the Anecdotes gives us a playful account of a day in the carrying business: the clerk starts very early, checking the barge and warehouses and opening the office; Man arrives later, and after lunch sends out for beer and tobacco from the Lower Ship Inn. Staff and clients relax, laughing, drinking, smoking, prating; the air grows thick, and one of the party peers through the gloom:

What thing is that I see,

Perch’d like a shuffle in a tree;

Or rather, like a candle snuff,

When just extinguish’d by a puff?

So meagre, sorrowful, and lean.

The mystery object proves to be Man himself, and this is the only clue we have to his appearance; but the joke may have been that he was actually portly ‘shuffle-wing’ was an old and apt nickname for the dunnock or hedge-sparrow.

In April 1802 the ‘New Canal’ shown on the Stranger’s map – the 500-metre short cut passing under Watlington Street and the King’s Road – was opened, and the Mercury tells us that ‘a barge freighted from London, belonging to the Navigation Company, on board of which was a great number of respectable inhabitants of this town, sailed up it. There was a blue flag and a laurel bough hoisted at the mast head, and the men were decorated with blue ribbons; she sailed to her moorings amidst a grand discharge of cannon .’

Afterwards the Navigation Company dined together in their office, where the day was spent with the ‘utmost festivity and hilarity’. In July 1804 the company asked for its sacks to be returned and encouraged debtors and creditors to settle up; it is not clear whether the business was folding. Man certainly retained an interest in water transport until at least 1811, when he was a signatory to a notice calling a meeting of ‘noblemen, gentlemen and other friends to the Thames Navigation’; they were concerned at the competition threatened by the many proposals for new canals. A list of Reading barge-owners in 1812 includes Blandy but not Man. Blandy became an alderman and mayor, and worked for the good of the town: he repaired Caversham Bridge and campaigned for the preservation of the Forbury as a public space.

Pen Man

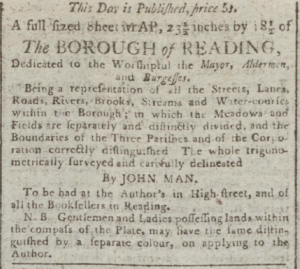

The idea of writing about his adopted town had already been in Man’s mind before he retired: he had for some time been collecting material for the Anecdotes and the History (see below). 1798 saw his first publication: a plan of Reading ‘trigonometrically surveyed and carefully delineated, engraved by W Poole and dedicated to the Worshipful the Mayor, Aldermen and Burgesses’. The lack of early maps is a constant disappointment to local historians: Reading’s first surviving plan is Speed’s of 1610, followed by an anonymous sketch-map of the Civil War defences in 1643. Rocque (1761) and Pride (1790) covered a wider area and have little detail of the town. Man’s pioneering effort used a bigger scale than any of these, but was soon eclipsed by the more accurate one by Tomkins, drawn for Coates’s History of 1802. In a corner of his map Man includes a note giving his estimate of the town’s population at 8350 (he was not far out: the first census in 1801 counted 9421).

In 1807 Man’s son William joined Robert Snare’s printing and bookselling business. The partnership produced a mixture of works, notably including things that might have displeased a less tolerant father: a supplement to Coates’s rival History; some verses by J B Monck upon the opening of the Literary Institution, rival to the Permanent Library (see below); and psalms and hymns edited by Henry Gauntlett, who (as we shall see) had taken exception to the Stranger. In 1816 William left Snare and set up on his own in Broad Street, but he printed very little more. At the age of 83 he married a 22-year-old on the Isle of Wight and fathered a daughter; he died in 1874. John’s wife Sarah died in May 1809. Details of their son Henry’s life are a little perplexing. In 1793 – when he was only 16 – Henry Man of Castle Street advertised himself as an importer of foreign spiritous liquors. In December 1797, according to John’s Anecdotes, ‘Harry the lad’, who’s seldom sad supplied the beer for the family’s New Year party. By 1808 he had progressed to London, and was married (by his old schoolfellow and bedfellow Thomas Dibdin) to Mrs Dennett, a widow with a small family. Dibdin says he died in 1810, but there are later extant letters; he clearly did not outlive his father, as he is not mentioned in John’s Will.

Both John and Horace were on the committee of the Reading Permanent Library, founded in 1807, which in the event proved decidedly temporary; the rival Literary Institution fared better. In 1809 John, William and Henry were signatories to a request for a meeting on Forbury Hill to discuss ‘the propriety of celebrating George III’s Jubilee’: they objected to Corporation-sponsored fireworks, and asserted ‘the right of the people to assemble and express their own sentiments, in their own style, on all public occasions’. (The political journalist William Cobbett made a similar complaint.) By 1810, the year of the Stranger -Man is listed in a Poll Book as a Gentleman, of Castle Street, having apparently moved back from the High Street. In 1816 he produced his History, insisting in his preface that he is ‘not an author by profession’.

Horace had taken a steady job as agent for the Globe Fire Office in 1804. He contributed to a fund for the relief of the poor in 1813, but otherwise there is no news until his death in 1817 at the age of 35 in ‘a melancholy accident’. He was sailing up to Pangbourne with two friends when they were caught by a strong wind, and the boom knocked him into the Thames. William took over his insurance job. John Man wrote an account of the churches of Wallingford in 1818; and died, aged 75, on 10 April 1824. The Mercury merely noted his death, with no obituary. His Will left two adjacent houses in Castle Street, then numbered 47 & 48, they were demolished to make way for the IDR roundabout – along with six cottages that he had built at the north end of the property, and also some land at Binfield which he had probably inherited. He had already given his books and instruments to William, and his furniture to his daughter Anna Maria; she remained a spinster until her death in 1860 at Jesse Terrace.

Two of John’s poem are reproduced below. First, his poem New Year’s Day in which he celebrates the coming year of 1798, and in which he mentions all his family and his father’s family recalling that his sister, Mariah, died early in 1797. The second is The Counting house mentioned by Adam Sowan above.

“My Wife” is Sarah (Baker) (1740-1809). “Maria” is John’s daughter Anna Maria (1780-1860). “Harry, the lad” is John’s son Henry (1776- ? ) who was in the wine business and thus ‘able to provide’. “dear Will” is John’s son William (1778-1874). “Horace” is John’s son Horace (1782-1817), who drowned in 1817. “Mamma” is John’s mother Mary (Balchen) (1721-1798). Note that this confirms that she did not die in 1790 as in the book “The House of Man”, but rather the date of 1798 that has been found by Ed Man. “Fenchurch Street” a reference to where John’s brother Henry (1748-1799) lived. Hal is Henry. “Walworth” is where John’s brother James (1755-1823) lived in 1797. “Ann” is his sister Ann (1753-1832), who moved to Reading. “Aunt Fanny,” may be John’s father’s youngest sister, Frances (1730- ?? ), who was born in Hurst and is one of the siblings of the father whose lives and deaths have not been found. “good lass – Fan” is, probably sister Frances (1757-1842).

New Year’s Day

Should frost and snows my walks oppose

The greatest ill I fear,

I’ll stay at home, no longer roam,

But hail the coming year.

Though I’m not great, I’ll sit in state,

And have my full career;

My pipe I’ll smoke, and crack a joke,

To hail the coming year.

My children all, and wife so small,

Aunt Fan without a peer;

We’ll ope our eyes to Christmas pies,

And hail the coming year.

My Wife I guess the fowls will dress,

If spoilt they will be dear,

If to my mind no fault I’ll find,

But hail the coming year.

Maria’s tarts will please all hearts,

As soon it will appear,

‘Tis such as her the wise prefer,

Who’d hail the coming year.

Harry, the lad, who’s seldom sad,

Shall furnish us with beer,

Or peg a tub of orange shrub,

To hail the coming year.

What shall we do, dear Will with you,

Your serious thoughts to cheer,

You drunk shall be, till you can’t see,

To hail the coming year.

Come Horace last, thou ne’er shall fast,

While mirth attends us here,

Your merry soul shall quaff a bowl

To hail the coming year.

Mamma so kind in me shall find

A love that is sincere

I’ll drink her health while I have wealth,

To hail the coming year.

May Fenchurch Street, enjoy a treat,

Hal’s Poetry and cheer;

If stocks go well, we all can tell,

He’ll hail the coming year.

To Wallworth next, I turn my text,

May James ne’er shed a tear;

His cash he’ll spend to treat his friend,

And hail the coming year.

There is one Man, whose name is Ann,

She comes in the rear;

On her I’l think whene’er I drink,

Or hail the coming year.

Oh! What a sot, I have forgot,

Aunt Fanny is most clear,

But if she’ll come, we’ll breach the rum

To hail the coming year.

Come fill a glass to a good lass,

Who thinks my notions queer;

‘Tis Fan I drink, who ne’er will shrink

To hail the coming year.

When next we meet at such a treat,

May death not interfere

But joys abound, and health go round,

To hail the coming year.

Dec. 27. 1797.

At the Line that mentions Ann in the original [Fan is crossed through]. The following poem describes a counting house in which John worked after he retired as a school master.

The Counting House

When early Phoebus mounts his car,

Will wakes, and spies him out from far;

With haste springs up, his breeches buttons,

And leaves the couch to drones and gluttons.

To Blandy’s wharf with haste repairs,

That wharf which swallows all his cares;

Surveys the barge with care about,

To find if ought is stolen out;

Since all is safe, from care is freed,

And goes to Maynard’s wharf with speed;

With eager steps he bustles on,

To enquire what work each man’s upon

And thus salutes them each in turn,

Here, Stevens, cleave this wood to burn:

Then see these sacks are stow’d with care,

And lay the sailcloth out to air;

Aye, this is something neat and clean,

A better store-house ne’er was seen;

But, let there be a nail or peg,

To hang this gridiron by the leg;

Who stole the axe, continual cries,

Beware the thief, if you are wise;

This kettle is worn out, ’tis true,

But still may serve to make a stew;

The Committee will no doubt agree

This door was well contrived by me;

Within this place, store pots and kettles,

Tan pins, hilts, and other metals;

Here’s room enough for all the tackle,

Be careful where you stow this shackle,

The marking-iron make red-hot,

To mark the powdering tub and pot;

But first, go light the counting fire,

Why Punch you are a cursed liar;

Within my veins my blood all curdles,

I thought you said, you piled the hurdles;

Is this the way, you stupid ass,

What cart or wagon here can pass?

Remove this hemp to yonder spot,

The dripping eaves may make them rot;

And why, how now, Hop,

Is this a time to come to shop?

Haste, mend your nimble steps, I pray,

We all were here by break of day;

This old tarpaulin’s almost ended,

With care, I’ll have it patch’d and mended;

This sail I see’s almost a rag,

But still may serve to make a dag;

Is Clements gone? Deuce take the noodle!

To take the barge without the loodle;

If Mrs. Plumridge comes, acqaint her,

We’ve all her tackle, but the painter;

Springall, this beech is rather dear,

We shall get nothing by it, it’s clear,

However, split it out for hilts,

The rest may serve to warm the tilts;

I’m glad to see you better, Dick,

Eating so hearty off the hick;

I thought, poor fellow, you were going,

Hilloah, Charles, what are you doing?

That cask must not go ’till it’s weighed,

Nor then, unless the money’s paid;

The man to me is quite a stranger,

However, send these plumbs to Granger;

The aqua fortis goes to West,

And Champion claims the yellow chest;

Observe to minute all things right,

Who careless is, gets nothing by it.

This sage advice, with freedom giv’n,

To counting-house he goes his Heaven;

Where James by this had made the fire,

And swep’t all clean to please the Squire,

Down in his elbow chair he squats,

And thus resolves his busy thoughts;

I cannot but this place admire,

So neat the curtains, snug the fire;

This shows what industry can do

The bridge from hence a charming view,

Twas kind of Blandy to pull down

The bulk that hid us from the town;

I like to see John Lewis loading,

So free a spirit needs no goading;

Another wagon, as I’m alive,

The deuce is in’t if we don’t thrive;

Poor Mills and Biggs, ’tis your own doing,

None but yourselves have worked your ruin.

At any time, to serve the town,

My life, I ready would lay down;

Tis true, I did contrive the plan,

But what of that! Oh! here comes Man;

Will. Are ye sure, friend John, you’re quite awake?

I fear, in bed, you’ve made mistake;

Upon my word, you’re up too soon,

It almost wants two hours to noon;

John. Why, let the stricken deer go weep,

On a good conscience I can sleep;

A wounded spirit, who can bear?

This makes you rise at four, with care;

Be sanctified like me, and then

I make no doubt you’ll sleep till ten;

Thus sports their little wits in play,

And, joking pass their time away;

Debate on politics, and Pitt,

Till business calls, then down they sit;

Their cash accounts to adjust with speed,

And carefully the invoice read;

Will. Enter, received a dozen poles;

John. For whom must Skinner bring up coals?

Will. First, set down ten for honest Phelp,

I love deserving men to help;

I’ll send to Clements quick a letter,

Pox take the pen, give me a better;

Item to Dreweat ten of coke,

Tis long since first they were bespoke;

Vines must have five, May’s promised ten,

Who load both ways are our best men;

Let Blackall have a five of each,

And Bushnell, for his five, go preach,

You stupid dog! What makes you slumber,

Quick, cast the whole, let’s know the number;

John. You are so hasty, Will, I doubt,

If I know well what I’m about;

They’re fifty, if I’m not mistaken,

Will. Then put another five for Bacon,

And five for Simonds make that plainer,

Then close the list with five for Tanner;

Next weighty business dispatching,

Will goes his rounds a money catching,

And leaves the clerk with woeful looks,

To post and rectify the books.

The morning past, the clock strikes one

The book are closed. the work is done;

Then homeward goes each busy sinner,

With appetite to eat his dinner,

Ten minutes end their frugal meal,

Whether of mutton, beef, or veal;

So short the time they have to tarry,

They scarce can speak to Tom or Harry;

When pleasure calls they never miss it,

Again the counting-house they visit;

Two chairs set out the best they’re able,

A four legged stool serves for a table;

On this they place in pretty order

Some broken pipes and pot of porter;

One rummer of a moderate price

Serves all the guests not over nice,

James Simonds takes the elbow chair,

A common one serves Will with care;

Willis and Man each mount a stool,

And Walter walks about to cool;

This conversation they commence,

Which shews they are all men of sense,

Walter. The king they say will not hear reason,

I fear he’ll drive the cits to treason.

Will. No doubt he treated them uncivil, Man.

The stocks are going to the devil.

Willis. I wonder what’s the price of wheat,

Will. I’ve bought the finest lot of meat;

Simonds. You mention meat, but what a pox,

I’d nearly lost a fatted ox;

He must to market while alive,

A sickly beast can never thrive;

Willis. To lose an ox no doubt is cross,

But I had almost lost my horse;

For going to Thame to buy some oats,

I meant to send by Reading boats;

Quoth Stroud, ‘We shan’t arrive to daie;

Unless I shew a shorter waie’;

So saying, down a lane he trotted,

My coat well dash’d, & splash’d, & spotted;

Till in a most unlucky minute,

I met a slough and tumbled in it;

Souse went my horse up to the saddle,

While I remained his back a-straddle;

When flouncing, kicking, spurring, whipping,

I got him out and saved a dipping;

However, my dapple’s rump is sore,

And mine is flea’d a foot or more:

When next I go to Thame for oats,

I’ll give you leave to cut your throats;

Walter. ‘This was no doubt a sad disaster,

Yet patience is a sovereign plaister;

When next you ride look well before,

Nor horse nor rider will be sore’.

Man. ‘John knows that industry brings wealth.’

Willis. ‘This brimmer James, to your good health.’

Simonds. ‘My pipe’s extinct, what must I do?’

Williams. Again replenish I’ll fill too;

But first examine, what’s the store?

My cargo’s out, we’ll send for more.

Man. You’re welcome to my box of tin,

Will. Without one single corn within!

Hoy Mother, (good woman, I should say)

To Lower Ship, you know the way:

Beer and tobacco, bid them send,

For Mr Williams and his friend:

How great the pleasure that I feel;

If I mistake not , here comes Neale.

In all his actions truth you’ll find,

A liberal heart, an honest mind:

But, hush! He comes, I must forbear;

Neale. Your servant, gents: how will you fare:

By this, I guess the scheme goes right,

Man. Come stick yourself behind a pipe:

Neale. Not now, thank you. What’s the news?

Will. This glass of beer you can’t refuse,

Tho’ it’s been brewed 6 weeks or more,

Most strange to tell, ’tis not yet sour,

Ah! John Harris too, are you come here;

Come, take a glass of Stephens’ beer:

Harris. I would comply without a joke,

But cannot see the glass for smoke;

Heavens! What thing is that I see,

Perch’d like a shuffle in a tree;

Or rather, like a candle snuff,

Then just extinguished by a puff?

So meagre, sorrowful, and lean,

Willis. It certain must be Man you mean.

At John’s expense the laugh goes round;

Who’d answer, but his wit’s aground;

Thus laughing, drinking, smoking, prating,

The day is spent without debating;

Till time, that enemy to glee,

Proclaims the hour of drinking tea;

When all retire but John and Will.

Who stay, their duty to fulfil:

Will sees the warehouses all sure,

And Man the counting house secure,

Then seek their families and friends,

And so the daily routine ends.

John Man, c1800, in unpublished volume of Anecdotes at Reading Public Library.

A few months after John’s death the Reading Mercury printed a spoof set of bye-laws, supposedly put out by the Paving Commissioners, about the maximum size of umbrellas etc. There is no doubt this was written by John and found in his papers by his son William. In his book ‘Letters from a Stranger in Reading’ John had spent quite sometime lambasting the state of Reading pavements.

However John’s concern with the sate of Reading’s paving was taken quite seriously by him as he also acted for a time as a Paving Commissioner. Evidence of this has been discovered by Adam Sowan, Reading historian, who has found at the Berkshire Record Office the minutes of the (unelected) Reading Paving Commissioners from 1785 (R/AS/1/1). The minutes reveal that John Man attended 17 meetings between 1796 (shortly after he retired from teaching) and 1810 (nine months after The Stranger appeared), though he evidently lost interest for three-and-a-half years between 1803 and 1807. The meetings he was at were almost all substantive, quorate ones at which some action was taken; twice he took the chair and signed the minutes. Only twice did he attend the abortive occasions, of which there were many, when insufficient commissioners were present and no business could be conducted; three or four regulars would meet in the Ship Hotel month after month, and no doubt enjoyed a glass or two. In June 1801 John joined a subcommittee to consider the best mode of lighting the town. After 1810 John’ name appears only once more, in 1821, when he was joined by his son William, who continued as a commissioner for some years after John’s death. This evidence shows John in a rather different light; it shows that he did try to change things through official channels and was not merely a passive complainer.

Reading Mercury, 26/07/1824

READING PAVING ACT

As the Commissioners under the Reading Paving Act have announced their intention to enforce the different provisions of that bill, it may interest our readers to be made acquainted with some of the clauses for their guidance.

This bill embraces many minutiae, which to superficial observers may appear puerile, but our thinking readers must be aware, how much less tractable is the comprehensive wisdom of modern Parliaments, than the glimmering light of ancient Wittengemotes; and dangerous consequences might result, if this intellectual tide of mental energy were dammed in Westminster; it is prudently therefore carried off in small channels, and sent flowing through the country for the edification of Rustics.

After various enactments relating to Pavements, Pent-Houses, and Scrapers, follows a clause regulating the honour of the wall:

Bakers and Chimney-sweepers are in no case to take the wall. – Ladies are always to be allowed the wall, on giving due notice of their intentions to take it. Inspectors are to be appointed who are to decide summarily in wall cases. When two gentlemen have dodged for three minutes without being able to pass, Inspectors are to interfere. Persons using sticks from necessity, are in all cases to give the wall to the stick. Switches are excepted. Exemptive clause in favour of crutches. Sticks out of use are to be borne perpendicularly, exception in favour of the yards of linen drapers, mercers, and men-milliners.

A clause to regulate the size and mode of carrying umbrellas. Not to exceed five feet in diameter. Umbrellas passing, are to slope to the wind. In a calm, the tallest to elevate; the Inspector to be provided with a measure to decide disputes. Persons under five feet are exempt from elevation. Little girls carrying Parasols under ten years of age in no case to elevate.

[This clause does not very clearly express whether the little girls or the parasols, are to be under ten years of age , the Commissioners construe it as applying to the latter. A descendant of Wat Tyler has applied for the office of Inspector, to determine who are little girls under the act.]

Umbrellas going head to wind, and poking out one or more eyes of a foot passenger, to be imprisoned a week and once well whipped.

Ladies bonnets are not to project more than seven inches from the head, two inches of trimming allowed. Leghorns or Cobbetts in their natural state, to be cut by inspectors.

Hoops found trundling on the pavement in dirty weather, to be seized and forfeited: half to the inspector. If the weather be dry, the drivers to be seized and the hoops re-turned. Little boys making beau-traps to be well splashed for the first offence second offence, transportation to the Forbury. No unqualified person to use a pea-shooter in the streets, under a penalty of five pounds, besides forfeiture of the engine and ammunition.

A penalty for hawking Mackerel in September; no person to cry in Reading under a penalty. Exception in favour of the bellman. A clause to regulate the height, &c, of Entrances: Outer-doors of freemen must be high enough to admit Mr. Palmer without his hat. Doctors’ knockers to be unhung at night. Horns of night Coaches to be muffled. Watchmen to whisper the time and weather.

There are various prohibitory clauses, among which is one strictly forbidding the Corporation to contribute a larger sum than one and threepence for the improvement of the narrow streets. An infringement on chartered rights to which that body will not probably submit.

There are several other clauses equally adapted to our present super-refined state of civilization and which we doubt not will ultimately render Reading a pattern-town for legislative politeness and municipal decorum.

John Man’s Letters to George Cumberland

ADD 36491 f 249 John Man to Geo Cumberland about 1775/6. The letter below is also found on John’s father’s page.

It is with the utmost pleasure and satisfaction dear sir that I now set down to answer you last obliging letter which I received a few day ago and would have answered soon had I had the opportunity. Since my brother has referred you to me I shall enform you of what I know concerning my father.

In December 1769 I went to him at (?Knighton?) and after that I received one letter from him or I believe two but cannot say for certain at this distance of time. But whether it was one or more I can safely assert I never received any from him or have heard of him by any other means since Easter 1760. I am very certain of the time because in the last that I received I was ordered to go to him for the rent of the houses there and I think it was 1st of May that I went however I am very sure it was sometime before I came to Reading and I came hear in June that year. This is all I know of the affair and I am pretty certain none of the family have heard of him since.

If I can be of any service to your mother I beg she acquaint me in what manner and be assured I shall exert myself to the utmost to delight her. I am very glad to hear that your brother is going to Driffielde because you give me reason to hope that the road through Reading will not be much out of the way. I flatter myself I should be welcome else should not presume to offer to attend you.

We are naturally fond of pleasure so it is no wonder if I catch at every opportunity that offers to gratify a passion which I inherit from my nature, if I can conveniently accommodate the journey to the beginning of our Whit Sun Holidays I shall be very happy to join you on the journey at Reading. I can then accommodate you with a bed which though none of the finest I can promise you shall be wholesome and better than travellers usually meet with at Inns. And we set off with the Sun and get to the vicarage by the time a fine little pig will be put to the spit. Since you say the west has attractive powers as well as the North I think I may be certain of seeing you in summer whether we go the journey or no therefore I shall use no arguments to persuade you to favour one with a visit which I think you have favoured on these 6 years but never yet fulfilled. But now I expect you in good earnest so take care you don’t disappoint me. When your brother was here I engaged to write to him but alas! Never thought to ask for his address whence it comes. I have not fulfilled my promise. Do you make my compliments to him and beg him to use the power of the keys (which in spite of the Pope I believe was given to him) in behalf of a poor persistent sinner who like other penitents is determined to transgress again . until the next time.

You and I George are now laymen and have nothing to do with religions dispute. We believed before Gibbons attacked our faith and I dare say were not staggered with his objections so stood in no need of Dr Watsons’ vindications. One of the Fathers [no matter which] said he believed in the Trinity because it was impossible but I believe in Christianity because it was founded by a divine power grew up and flourished in opposition to principalities and powers and by its own internal evidence has withstood the attacks of (?Deistoltsheists?) and unbelievers. Compliments to your mother & brother & C

from your affectionate cousin

Jno Man

Addressed to: Mr. Cumberland

Secretary’s Office at the Exchange Assurance Office, London.

Dear Sir,

The ill success of your negotiation is no reason why I should not return you my hearty thanks for the trouble you have taken in it. I should have been very happy to have had it but must do as well as I can without it. I know that the little concerns of this life will in a few years pass away like a dream but like most men I could wish to make it a Golden one. Your account of your brother is so very flattering that I confess I envy him his employments, his amusements, his studies, his everything. His is a situation for wise men to emulate for Philosophers to enjoy. I beg my love to him when you write and assure yourself of the sincere regard of your affectionate humble servant

John Man.

ADD 36497 f 67

John Man to Geo Cumberland 12th November 1791

Dear Sir,

After so longer silence I had given up all hopes of hearing from you when I received yours for which favour I find I am indebted to my old friend Bardello. But from whatever motive it proceeded I am equally gratified in the pleasure of hearing from you and renewing correspondence which ought never to have been interrupted had I not been bound by the leg like a bear. I had certainly made a pilgrimage to Lyndhurst in the summer but my chains are of such a nature that much fear of travelling even on foot was not invented for me. Yet if God in a reasonable time should set me on horseback my first scamper should be to your house. I long for that tete a tete you speak of for an opportunity to talk with you of things past and present and to come I am impatient to take a view over your management now you are become a family man. I should expect to see the beaten paths of unthinking men give way to the less trodden tracks of Philosophy but different from that of the proud peevish delectable Jean Jacques singularly of conduct seemed to be his Prose Star which alone he pointed his way. Diogenes roll’d himself in snow when men less wise (in his idea) were sitting comfortably by their fireside and in the same spirit of Rousseau parted with his children to the hospital never to see them more and why! Because nature has all men to cherish their off spring may such Philosophy be damned I say. I know no use of philosophy but to make us better or happier and it is of that sort I expect to find at Lyndhurst if I am ever so happy as to see you there in the meantime as the Mountain will not come to Mohamet cannot he come to the mountain. Upon a moderate computation, Reading cannot be more than 10 miles out of your way to London where you must go sometimes and I hope to have always a bed at your service and 10 months in the year you will find me at home. So come away and let me at least improve by the history of your travels. The book will I fear be of no use to you because several leaves are lost at the end. But as I cannot understand how many you want I have sent it as you desire to Mr Shelly’s with the 2 last volumes of the Tableau which are all I have of yours. If I hear anything likely to write you will give you a line but everything of this kind sells immensely dear. Your best way will be to write to Kimberley Auctioneer at Windsor. I am not acquainted with him but to judge by his advertisements in our paper he has all the Estates in the County to sell.

You mention your brother in your letter else I should not have known he was still on this side of the river Styx. Not having heard of him for near two years no doubt he too is become a domestic man and perhaps may think rocking the cradle as much a diversion as travelling. However it is, I am almost convivulated and my connections confined to my own little family. That you and yours may enjoy every blessing this side of eternity is the hearty wish of your affectionate.

Jno Man